ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (ACM FAT*) is a “multi- disciplinary conference that brings together researchers and practitioners interested in fairness, accountability, and transparency in socio-technical systems.” The conference originated from a fairness workshop in machine learning workshop at NIPS a few years and last year they had the first inaugural event as an independent conference. This year, they were joined with ACM and it was held in Atlanta, GA in Jan 2019. I attended both the tutorials and the main conference.

General thoughts

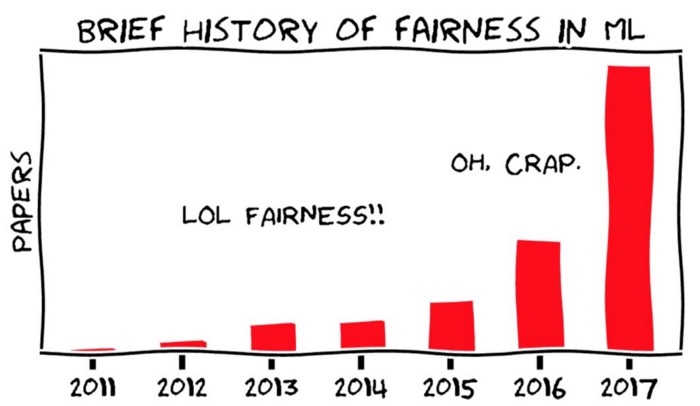

Compared to the last year’s conference, which I also attended, it seemed that the academic discipline has become more mature; last year, there were many talks focused on showing the examples of biased machine learning in practice and researchers discussed how they can agree upon defining terms such as fairness in mathematical concept. This year, there were many in- depth theoretical studies where researchers built mathematical models to simulate the propagated effect of bias in machine learning (ML). Empirical studies were also presented as well, in which researchers crowd-sourced data to show bias in human judgment especially when they interact with ML algorithms. Unfortunately, due to the recent long-term government shutdown, there weren’t many government officials who were supposed to participate. Hence, it was lacking to see how the discoveries made in academia can be translated into actual policies and legislation. However, it’s important to notice that there is huge growing interest in this field as ML-based algorithmic decision making is widespread in our society.

Tutorials

For tutorials, I attended the Translation Tutorial: A History of Quantitative Fairness in Testing and Hands-on Tutorial: AI Fairness 360 Part 1 and Part 2.

The tutorials are divided into two categories: translation and hands-on. Since the conference is multi-disciplinary, there are attendees from various backgrounds; computer science, social science, law and policy, etc.

Translation Tutorial: A History of Quantitative Fairness in Testing

The translation tutorials are designed to have everyone more or less be on the same page. This specific translation tutorial I attended seemed to be aimed at computer scientists who are not much aware of the history of research on fairness and automated decision making. This was given by Google researchers Ben Hutchinson and Margaret Mitchell, who showed that the growing current interest on fairness in ML isn’t something new but existed in 1960’s when the civil rights movement started, which made sense.

Then, the interest was on designing fair standardized tests like SAT or LSAT. Based on correlation studies, researchers then discovered that standardized tests require specific cultural knowledge, which is unfair to racial minorities. There were several views on how to build a fairer model, similar to the various modeling perspectives found in modern studies, such as whether to use sensitive features like race or gender exclusively in models. Also, researchers then pointed out that what we are trying to predict and what we should do are two different questions, which is always mentioned in almost every presentation at this conference.

Ben and Margaret finished the talk by inspiring the audience with various research opportunities that we can learn from the history. For instance, these historical studies started by asking the question of “what is unfair?” instead of the definition of fairness itself. Correlation- based approach and addressing regression problem (instead of classification) in fairness are other examples.

Hands-on Tutorial: AI Fairness 360

The second tutorial I attended (“AI Fairness 360”) was a hands-on one. Here, I learned about IBM Research’s effort to build an open-source Python package that implemented mathematical definition of various fairness criteria and how to apply them to a user’s existing workflow. The package seemed quite comprehensive and had great usability for the following reasons:

- There is no one definition that satisfies all the needs and hence they have implemented a variety of metrics.

- The package addresses different steps in ML pipeline where the fairness adjustment (i.e., mitigation algorithm) can be made: pre-process (mitigation to training data), in-process (mitigation to model during training), post-process (mitigation to predicted labels). This gives freedom and flexibility in the mitigation process.

- Its syntax is similar to scikit-learn, which make everything easy and familiar. Plus, their API is well-established, and the repository has many notebook examples.

- The package can have various types of data (tabular, images, etc.)

This is just a start and of course, there are aspects that can be improved and investigated. First, some mitigation algorithms require tuning. It’ll be interesting to understand how this works on top of the main ML model’s tuning process. Since there are various fairness metrics, it would be nice to directly target those metrics for tuning. When a mitigation algorithm is applied, we sometimes see a compromise in model performance. In this case, it will be interesting to conduct an error analysis to find in which examples the model starts missing predictions.

Keynote

There were two keynotes from two very different domains: computer science and law. The computer science one was given by Jon Kleinberg at Cornell University. His talk was about mathematical formulation of a mitigation policy called Rooney Rule. The Rooney Rule is a requirement that at least one of the finalists be chosen from the affected group. His researched showed that it not only improves the representation of this affected group, but also leads to higher payoffs in absolute terms for the organization performing the recruiting. He presented a mathematical proof to prove his point. His model has only three parameters: composition of pool (diversity), level of bias, and abundance of outliers (superstars) and he showed that with certain constraints, Rooney Rule can be used to improve to the utility of the entire group (not just for the minority).

The second one was given by Deirdre Mulligan from UC Berkeley. Her talk was on “fostering cultures of algorithmic responsibility through administrative law and design”. She started by citing the case Loomis v. Wisconsin where Eric Loomis challenged the State of Wisconsin’s use of proprietary, closed-source risk assessment software (COMPAS) in the sentencing of himself to six years in prison. His argument was that there was gender and race bias in the software, which was also addressed by many investigative journalists. One of the interesting and disappointing part of this case was that the court addressed that “it is unclear how COMPAS accounts for gender and race…”, meaning the lack of transparency of the software but also the lack of ability to handle these cases in law. To fix this problem, she emphasized that there should be case laws addressing limits and details of math and algorithms, but more importantly, a “contestable” design. This means whenever there is a wrong done to a person by automated decision, they should be able to contest on this algorithmic decision.

Main sessions

In total, there were 11 sessions and there was a wide range of topics ranging from problem formulation to content distribution and economic models. The following sessions stood out.

Framing and Abstraction

The talks in this session here mentioned that problems in ML projects can start from the very beginning where ML practitioners and data scientists start formulating ideas and framing problems. For examples, if what one wants to measure cannot be obtained or measurable, they use a proxy that is correlated to the original metric they wanted to measure. Sometimes data scientists transform a regression problem as classification by discretizing variables. Unfortunately, these decisions are often not well documented even though they happen in many layers in a ML project.

Profiling and Representation

Chakraborty at al. presented an interesting idea of handling online trolls in their talk, “Equality of Voice: Towards Fair Representation in Crowdsourced Top-K Recommendations.” Since algorithms trained by online user data make often offensive and biased prediction, they came up with a fairer “voting” system by considering that there are a few bad actors (the trolls) and that most users are silent (who don’t case a vote). Here, the main challenge was the latter because they need to infer how a silent user might have voted. To solve this, they used existing personalized recommendation techniques.

Fairness methods

In “From Soft Classifiers to Hard Decisions: How fair can we be?”, Canetti at al. tackles the fairness problem by implementing a deferral process. Instead of making hard yes/no decisions, the model can defer the decision to a group of moderators so that they can gather more information and make more socially-acceptable decisions. Their paper discussion a couple of options of deferrals: applying different thresholds per group for deferral or equalizing the accuracy with equal deferral rate.

Similarly, in “Deep Weighted Averaging Classifiers”, Card et al. questions when we should know when not to trust a classifier. On top of traditional model performance, they come up with a separate measure of model credibility which can address whether this model is a right tool. They provided a fun example where they build a model by using the MNIST dataset and then used the trained model on the Fashion MNIST (the former has images of numerical digits and the latter, images of clothes and shoes). The model can still make predictions but clearly this model is not built for the testing data. In this case, the model’s “credibility” is very low.

Explainability

Ustun at al. points out that explanability does not mean contestability in their talk, “Actionable Recourse in Linear Classification”. When a model explains why your loan is rejected, it doesn’t mean what you should do about it, especially the explanation is based on immutable features like your race. They suggest that we should have a system and model that provides “ability to obtain a desired prediction from a model by changing actionable input” so that the model’s explanation is actually useful. Their tool provides two answers: 1) what users can do to flip the decision and 2) the proof of no recourse (by checking every option in actionable features). The second answer can be still valuable because then it provides the user with contestable information.

Economic Models

There were two dedicated sessions just for economic fairness, new to this year’s program compared to the last year’s. One interesting concept discussed in multiple talks was “strategic manipulation.” It is also called “Stackelberg game”, where candidates might try to change their feature to game the system (the model) and the learner anticipates this and adjust the classifier by changing the decision boundary more stringent, which can also result in changes in candidates’ behavior. Milli et al.’s discussed in “The Social Cost of Strategic Classification” that so far the approach to this problem has institutional-centric view. For instance, when the institution, who build the model, wants to come up with a counter-measure to strategic manipulation, they weigh hard-to-change features such as parents’ income or zip code more highly. Then it becomes extremely high-cost for credit-worthy individuals in the wrong zip code area to obtain a loan, meaning the social burden is now on individuals. Their study found that as the game is played, individual social burden increases and returns more unfair outcome.

Summary

I enjoy this conference very much not just because of personal interest but also of the fact that studies discussed here emphasize robustness and responsibility of ML algorithms, often ignored in ML community. Plus, the crosstalk between different domains enlighten me because they the topics can be applied to many aspects of ML engineering work. The theoretical studies provide new insights on how to measure abstract concepts like fairness and bias, transferrable to processes like problem statement that are highly important in ML. The empirical studies help theoretical studies grounded and more realistic. Finally, the law and policy side of works emphasizes the real implementation of these studies, which resembles constructing deployment plans and the results with stakeholders.