ML for efficient hardware verification

One of the main challenges of hardware verification is finding bugs efficiently in a design. Since verification is resource-intensive in hardware engineering, ML for hardware verification is an active area of research. The mainstream idea in research is using reinforcement learning (RL) even though it is challenging to productionize RL.

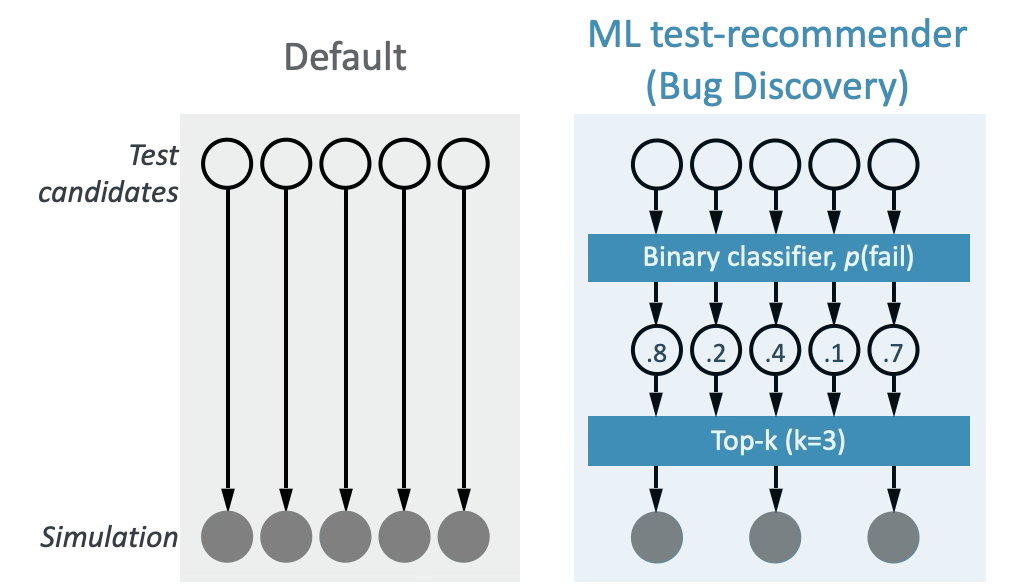

Instead, my team at Arm developed an ML application based on a simpler approach: supervised learning with recommendation (Figure 1). The model uses binary fail/pass labels during training, and predicts the probability of a test candidate being a bug. In production, the application makes batch prediction of a set of candidates and ranks the prediction scores so that engineers run only a subset (top-K) while discovering similar number of bugs.

Objectives

Since verification is an exploration problem, its success is measured by the number of novel bugs discovered. Each verification test returns a binary label: fail or pass. When a test fails, it returns a failure signature (often called a unique fail signature, or UFS), which summarizes the cause of the failure. The business objective of bug discovery can be expressed mathematically as maximizing cardinality of the fail signature set \(\{s_i\}\) from \(K\) test candidates:

\[ \left|\bigcup_{i=1}^{K} \{s_i\}\right| \tag{1}\]

So far we have been addressing this in a binary classification framework where we use the fail (1) and pass (0) labels. This is based on empirical findings which suggest positive correlation between the number of failures and the number of UFS. In other words, in the binary classifier, we aim to maximize the number of failures given \(K\) test candidates:

\[ \sum_{i=1}^{K} \mathbb{1}_{y_i = 1} \tag{2}\]

Shortcomings of binary classification

Once we deployed the classifier, we unfortunately started observing frequent fluctuations in model performance, often with suboptimal outcomes. After model inspection, we learned that the training process was often dominated by frequently-occurring failures. It turns out the fail signature frequency distribution has a long tail, indicating that only a small number of fail signatures dominate the failure-label space. Therefore, the model learned patterns from a small number of failure signatures.

From business perspective, this is problematic because frequently-occurring failures are already well known to verification engineers. These bugs are also not caused by design but other factors such as testing infrastructures. In other words, when the model focuses on these failures, our application delivers low value and may even risk misclassifying rare (more valuable) failures as passes, failing to prioritize them.

Learning to rank bugs by their rarity

When I was looking into ways to fix this model behavior and have it focus on rare failures (bugs), I learned about learning-to-rank (LTR) algorithms, a family of supervised learning algorithms that learn to generalize the ranking of samples. In a typical LTR dataset, labels are often integers that represent relative relevance of samples in a dataset. Their loss function usually focuses on the top-K elements, and tries to optimize an information retrieval (IR) metric. One of the most widely used IR metric is normalized discounted cumulative gain (NDCG), the normalized version of DCG, which is defined as:

\[ \text{DCG}_K = \sum_{i=1}^{K} \frac{2^{rel_i} - 1}{\log_2(i + 1)} \tag{3}\]

where \(rel_i\) represents the relevance label of the \(i\)th sample.

Inspired by this, I formulated our objective as a ranking problem. I created a new labeling function that returns integer relevance labels by thresholding fail signature frequency. Failed tests whose signature frequency is less than \(M\) times were considered rare. Other failed tests were considered common failures, and passing tests irrelevant. The LTR model learns to rank samples based on these relevance labels. It prioritizes rare fail signatures first, then common failures, and lastly passing tests. An important modeling assumption here is that there might be a learnable pattern among rare failures.

I soon realized that the gap between optimization metric (model loss) and target metric (Equation 1) is reduced with the LTR model compared to the binary classifier (Table 1). In addition to not incorporating failure signatures, the binary classifier neither learns ranking directly nor only focuses on top-K during training. The LTR model address both and can return higher cardinality by prioritizing rare signatures.

| Target metric key characteristics | Target metric addressed by classifier loss? | Target metric addressed by LTR loss? |

|---|---|---|

| Cardinality | No | Partially Yes: Rarity prioritization leads to higher cardinality |

| Fail signatures | No: Uses binary labels | Yes |

| Ranking | No | Yes |

| Top-K | No: Uses all samples | Yes |

Data augmentation with simulated LTR groups

A typical LTR dataset has a group (or query) variable that indicates the group membership of a given sample row. During LTR model training, the loss is calculated per group, and its aggregate is used for model updates. It’s like we want to teach a search query model to prioritize similar types of items across multiple different queries. It is technically possible to create a single group that contains the entire training dataset. However, this is much more challenging in terms of both loss optimization and compute. Besides, sometimes it’s not supported by model libraries. For instance, the lightgbm package limits the group size to 10k.

In the verification training data, there are a few candidate features to group the samples. However, I decided to adopt a simpler approach: bootstrapping. I created an augmented training dataset with \(m\) groups where each group contains ALL rare failures, a subset of common failures, and a subset of passes where the subsets are bootstrapped independently across all groups. I chose this particular method of guaranteeing every group to have all rare failures because the model should learn to prioritize these over the rest. The details of this process is shown below:

Input

\[ \begin{aligned} & D_{train}: \text{Original training dataset} \\ & F_{rare} \subset D_{train}: \text{Set of rare failures} \\ & F_{common} \subset D_{train}: \text{Set of common failures} \\ & P \subset D_{train}: \text{Set of passes} \\ & k_{common}: \text{Sampling size of common failures} \\ & k_{pass}: \text{Sampling size of passes} \\ & m: \text{Number of groups} \\ & s: \text{Fixed size for each group where } s = F_{rare} + k_{common} + k_{pass} \end{aligned} \]

Output

\(D_{aug}\): Augmented training dataset

Procedure

- Initialize \(D_{aug} \gets \emptyset\) with size \(s\)

- For \(i = 1\) to \(m\):

- \(D_{aug} \gets F_{rare}\) (Include all rare failures)

- \(D_{aug} \gets D_{aug} \cup \text{RandomSample}(F_{common}, k_{common})\)

- \(D_{aug} \gets D_{aug} \cup \text{RandomSample}(P, k_{pass})\)

- Return \(D_{aug}\)

This bootstrapping process naturally results in bagging (bootstrap aggregation) effect. The training dataset now has synthetic bootstrapped groups, and the LTR model has to learn to prioritize rare failures over different combinations of common failures and passes.

Benchmarking with production datasets

With this new LTR model, I conducted a benchmarking experiment to compare the model performance of the existing binary classifier and the new model. I used about 40 production datasets from a CPU project from last year. For a thorough model comparison, I used the following four metrics:

- Number of failures (Equation 2): Binary fail/pass

- Number of rare failures: failures whose relevance label is the largest \[ \sum_{i=1}^{K} \mathbb{1}_{y_i = \max(rel)} \tag{4}\]

- Number of unique fail signatures (Equation 1): Measure of signature set cardinality

- Number of never-seen fail signatures: Number of signatures that are newly discovered in the test set but NOT observed in the train set, \(S_{train}\) \[ \left|\bigcup_{i=1}^{K} \{s_i\} - S_{train}\right| \tag{5}\]

These metrics allow us to understand different aspects of model behavior. The number of rare failures (Equation 4) addresses ranking quality most directly. The number of unique fail signatures is our KPI. The number of never-seen fail signatures indicates model generalizability.

Ranking performance comparison

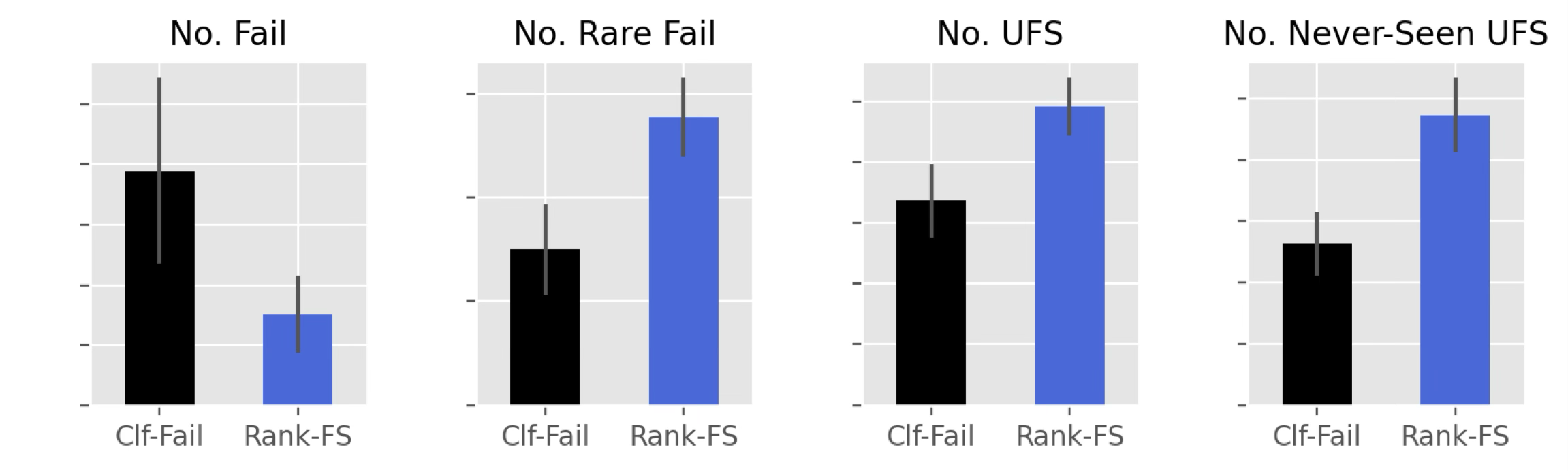

The average performance of the four metrics of the two models shows an interesting pattern (Figure 2). Although the classifier is much better at capturing failures than the LTR model (leftmost), when it comes to metrics that consider fail signatures, it was worse than the LTR model. This supports the idea of the large metric gap of the classifier’s model loss and the target metric (KPI) (Table 1).

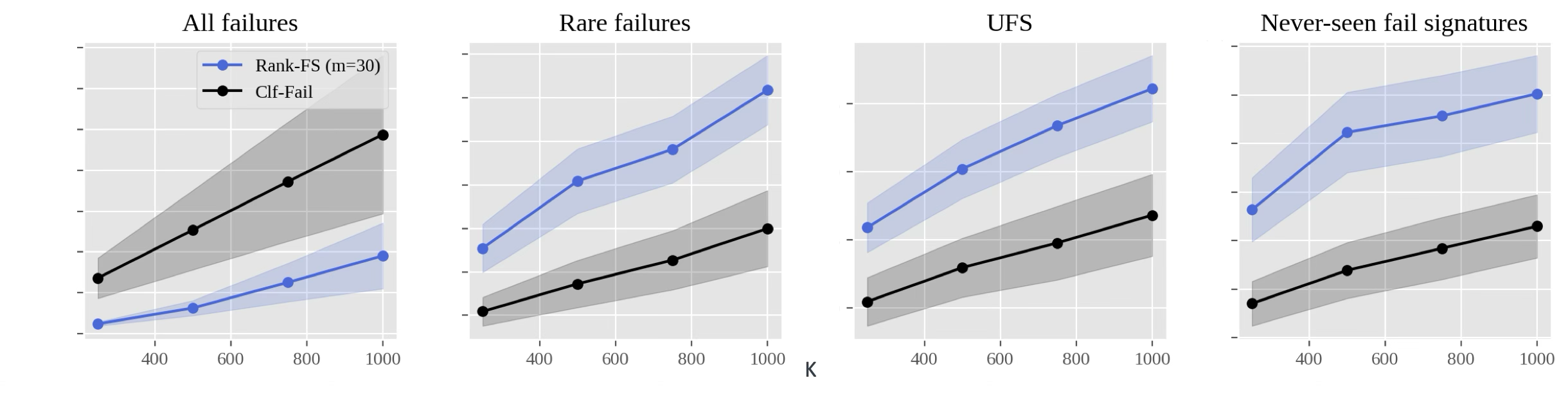

This performance pattern remained consistent when I varied K (Figure 3). By comparing different Ks, it’s possible to measure efficiency improvement by the LTR model. In the “UFS” and “Never-seen fail signatures” plots, the LTR performance at \(K=250\) is similar to the classifier performance at \(K=1000\). This suggests that the LTR model may require 75% fewer tests to produce the same results.

Measuring the bagging effect

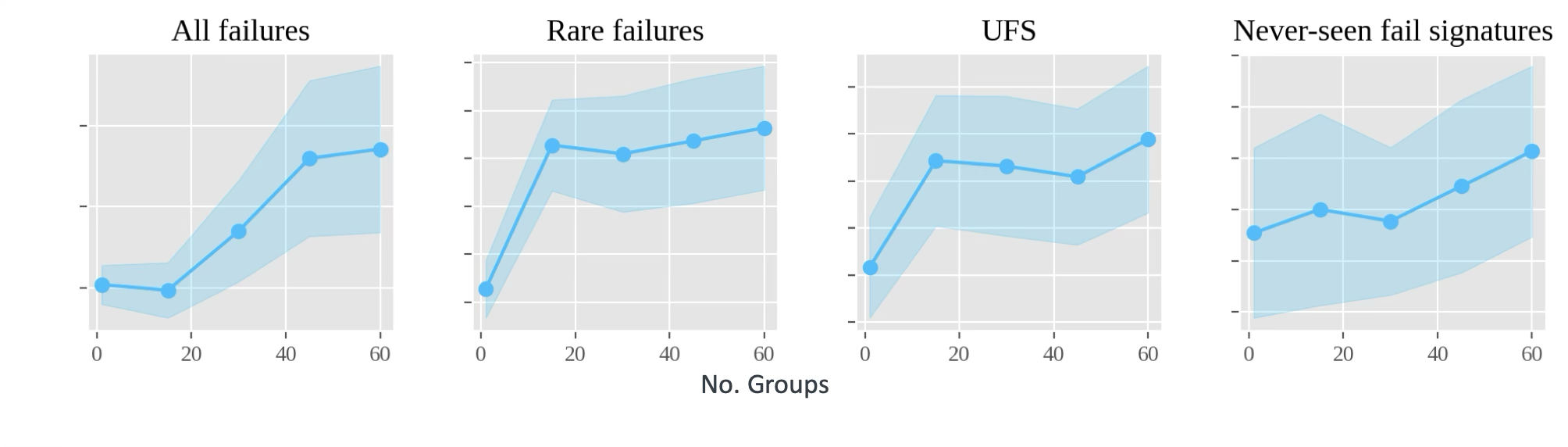

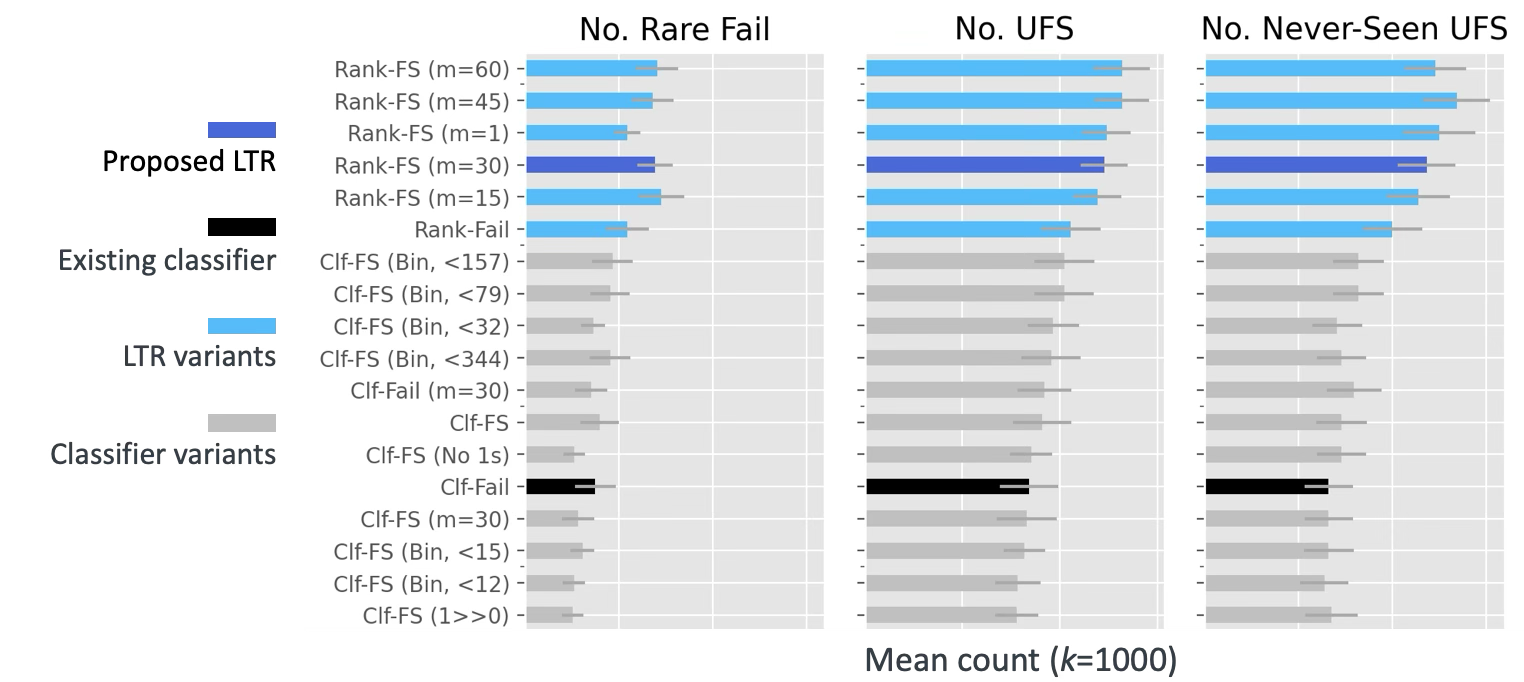

In the default LTR model version I tried, I created a training dataset with 30 bootstrapped groups. When I varied the number of groups, I observed the impact of bagging on model performance (Figure 4). As I increased the number of groups, the performance generally improved but it had diminishing return after a certain point.

Extended model comparison

To further understand the model behavior, I created several model variants and measured their performance using the same metrics and benchmark datasets.

Separating the impact of label change and algorithm change

In the LTR model, I made two changes. I created a different labeling system using failure signature frequency, and I changed the algorithm from classification to LTR as well. To separate the impact of these changes, I created two model variants:

- Multi-class classification with relevance labels (“Clf-FS”)

- LTR with binary labels (“Rank-Fail”)

Classification with frequency-based label encoding

To further explore the idea of the impact of the new labeling system I used for LTR, I tried the following two classifier variants:

- Binary classification without “common” failures (“Clf-FS (No 1s)”)

- Binary classification by treating “common” failures as passes (“Clf-FS (1>>0)”)

I also played with different signature-frequency thresholds to create binary labels. For instance, if the threshold is 50, all failures whose signature frequency is less than 50 are labeled as 1, the rest (failures whose signature frequency is larger than 50 and all passes) are labeled as 0:

- Binary classification with varying signature-frequency thresholds (“Clf-FS (Bin, <\(N\))” where different Ns are chosen based on varying quantile values)

Classification with bootstrapping

To investigate whether bootstrapping can improve classification performance, I created the following variants as well:

- Multi-class classification with relevance labels and bootstrapped training data (“Clf-FS (m=30)”)

- Binary classification with fail/pass labels and bootstrapped training data (“Clf-Fail (m=30)”)

The verdict

Figure 5 shows the final model comparison that includes all classifier variants (gray) and LTR variants (light blue) in addition to the existing binary classifier model (black) and the first (default) LTR model (dark blue). Modifying the label encoding slightly improved the performance of classifiers (see “Clf-FS (Bin, <\(N\))” models in the middle), but their performance was still worse than all LTR variants. Interestingly, the LTR model that used binary labels (“Rank-Fail”) was better than the existing binary classifier’s performance, suggesting that direct ranking optimization result in better performance since our key metrics are ranking metrics.

Conclusions

One of the biggest lessons from this project was the importance of reducing the gap between the business objective and the optimization objective of ML models especially when it is challenging to accommodate the former. By switching from binary classification to learning-to-rank, we achieved similar bug discovery rate with 75% fewer tests, while better identifying rare and never-seen failure signatures. The LTR model’s success in learning patterns among rare failures suggests there may be underlying commonalities in these rare failures that require further investigation.

The lightweight nature of our approach - using only test settings without design features - makes it particularly practical for verification teams. While not attempting to fundamentally solve the verification problem like RL studies, this approach offers a more deployment-friendly solution that allows verification engineers to focus their efforts on more challenging bugs. Future work could explore incorporating design features, LTR model fine-tuning, and using test output features for ranking.