Everyone says you can build an agent in several lines of code. Making it work in production is a different story. APIs timeout, LLMs hallucinate recovery strategies, users provide incomplete data, and the workflow needs to handle all of it gracefully without cascading failures.

In traditional software, you catch exceptions, log them, and maybe retry. In agent systems, this approach does not work efficiently because the right recovery strategy depends on error semantics, not just error types. For instance, a timeout should retry automatically, but an “email format invalid” error needs semantic understanding to fix. Besides, for a problem that requires human intervention, the system needs to pause and seek out human input. This differs depending on whether you need information from users or need developers to debug the system.

Agent workflows are multi-step and autonomous. An error in an intermediate step shouldn’t just bubble up. It might need retry logic, LLM reasoning to adapt, or user clarification to continue. Treating all errors the same leads to cascading failures or stuck workflows. This post covers four error handling patterns for LangGraph agent systems, each mapping to a fundamentally different recovery mechanism:

- Retry with Backoff (Time-based): wait and try again (no decision needed)

- LLM-Guided Recovery (Semantic): LLM reasons about context and chooses action

- Human-in-the-Loop (External information): only humans can provide what’s needed

- Unexpected Failures (Unrecoverable): surface to developers immediately

This post is inspired by a LangGraph tutorial. The tutorial covers basic concepts of the errors but not the full practical implementations. In this post, we will discuss a more detailed walkthrough of each error type such as when to use each pattern, code examples for different workflows, and architecture for testing error scenarios.

We’ll use the familiar and simple email support agent (the same one from the above-mentioned tutorial) as an example throughout. This way, we can focus on error handling patterns rather than understanding complex business logic.

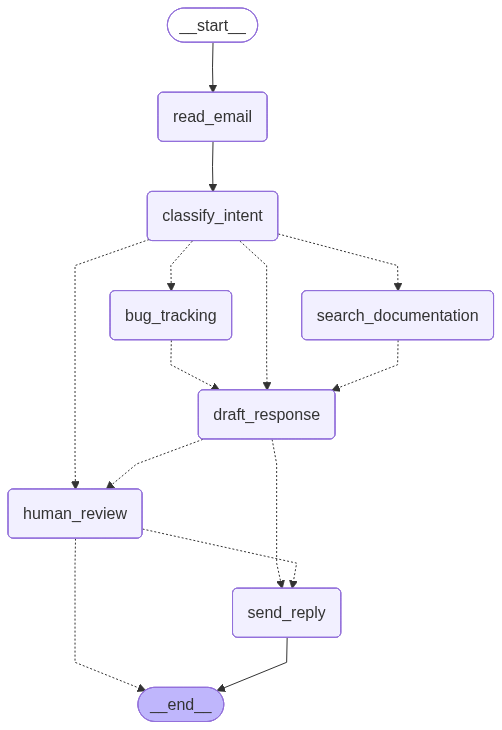

All code is available here. The figure below shows the workflow overview of the email support agent system.

LangGraph Quick Start

Core Concepts

Let’s quickly review the key concepts of LangGraph.

1. State = Workflow Memory (Data)

State is a typed object (Pydantic model or TypedDict) that flows through your workflow; I prefer Pydantic over TypedDict for runtime validation and better error messages. Think of a state as a comprehensive list of data fields in your agent system. You should be able to fully design the system first before defining a state. Every node reads it and returns updates:

from pydantic import BaseModel

class EmailState(BaseModel):

email_content: str

sender_email: str

classification: dict | None = None

draft_response: str | None = None

reply_sent: bool = False2. Nodes = Processing Functions

Nodes transform state and return updates. Each node reads the current state, performs a specific task (like calling an API or running an LLM), and returns updates to merge back into state:

def classify_email(state: EmailState) -> dict:

"""Returns dict; updates merged into state."""

classification = llm.invoke(state.email_content)

return {"classification": classification}3. Command = State Update + Routing

The Command lets nodes do two things at once: update the state AND decide where to go next. Without Command, nodes only return state updates and go to pre-defined edges. With Command, a node can make routing decisions dynamically based on what it just processed. This is useful when the next step depends on the results of the current node:

from langgraph.types import Command

def classify_email(state: EmailState) -> Command[Literal["search_docs", "bug_tracker"]]:

"""Returns Command; updates state AND decides next node."""

classification = llm.invoke(state.email_content)

next_node = "search_docs" if classification.intent == "question" else "bug_tracker"

return Command(

update={"classification": classification},

goto=next_node # Dynamic routing

)4. Workflows = The Big Picture

Workflows connect all your nodes together into an execution graph. Using StateGraph, you define which nodes exist, how they connect to each other, and the order of execution. Think of it as drawing a flowchart; you specify the starting point, the processing steps (nodes), and the paths between them (edges). Once you compile the workflow, you have a complete agent system ready to execute:

from langgraph.graph import StateGraph, START, END

workflow = StateGraph(EmailState)

workflow.add_node("classify", classify_email)

workflow.add_node("search_docs", search_documentation)

workflow.add_edge(START, "classify")

workflow.add_conditional_edges("classify", ["search_docs", "bug_tracker"])

workflow.add_edge("search_docs", END)

app = workflow.compile()You can visualize workflows in several ways. For command-line scripts, print(workflow.get_graph().draw_ascii()) outputs an ASCII diagram directly to the terminal. For richer visualizations, workflow.get_graph().draw_mermaid() generates Mermaid diagram code you can paste into mermaid.live. For Jupyter notebooks, compiled workflows’ diagram can be rendered in output cells (i.e., simply return app in a cell).

5. Execution

Once you’ve compiled your workflow, call invoke() with your initial state and the workflow runs through the graph. This executes nodes and follows edges until it reaches the END. You get back the final state with all updates from every node that ran:

result = app.invoke({

"email_content": "I forgot my password",

"sender_email": "user@example.com"

})

print(result["draft_response"])Note that LangGraph workflows are compiled. Once you call .compile(), node functions are locked in. To test different behaviors (like error simulation), you must rebuild the workflow with different node implementations. This is why modular architecture matters.

Testing Pattern: Workflow Builders

Since workflows are compiled and immutable, testing different behaviors requires rebuilding with node overrides. The build_workflow() helper function constructs and compiles a StateGraph while allowing you to swap in different node implementations for testing:

# Production version

app = build_workflow()

# Test version with simulated error

app = build_workflow(

nodes_override={"search_docs": search_with_error}

)This pattern keeps production code clean while enabling deterministic error testing. Examples throughout use this approach. Full code structure available in the [GitHub repo].

Observability Tools

LangGraph workflows benefit from observability tools that trace execution, inspect state at each step, and visualize error scenarios. LangSmith Studio is the primary tool for this. It provides real-time execution traces, state snapshots at each node, and visual debugging of workflow paths. To enable tracing, set your LangSmith API key and configure tracing before building your workflow. Once enabled, every workflow invocation automatically logs to LangSmith, where you can inspect the full execution graph, timing data, and state transitions:

import os

os.environ["LANGCHAIN_TRACING_V2"] = "true"

os.environ["LANGCHAIN_API_KEY"] = "your-api-key"

os.environ["LANGCHAIN_PROJECT"] = "error-handling-demo"

app = build_workflow()

result = app.invoke(initial_state) # Automatically traced to LangSmithNote that this tracing is available for notebook code cells.

Error Handling and Recovery Patterns

Overview: The Decision Framework

Here’s a quick reference for matching error types to recovery patterns:

| Pattern | When to Use | LangGraph Feature | Recovery Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retry with Backoff | Network failures, rate limits, temporary outages | RetryPolicy |

Automatic retry with exponential backoff |

| LLM-Guided Recovery | Errors with semantic context LLM can understand and fix | Circular routing | LLM decides recovery action |

| Human-in-the-Loop | Missing data only user can provide, high-stakes decisions | interrupt() |

Pause and request human input |

| Unexpected Failures | Unknown errors, bugs, critical infrastructure failures | Exception bubbling | Log context, bubble up to developers |

Pattern 1: Retry with Backoff

This pattern uses automatic retry with exponential backoff to handle transient failures like network timeouts, rate limits (429), and temporary service outages (503).

The key is to use RetryPolicy when adding a node to a workflow:

from langgraph.types import RetryPolicy

workflow.add_node(

"search_documentation",

search_documentation,

retry_policy=RetryPolicy(max_attempts=3, backoff_base=2)

)The backoff_base parameter controls exponential backoff timing: backoff_base=2 means wait times follow 2^0=1s, 2^1=2s, 2^2=4s, etc.

The workflow attempts the failing node 3 times with exponential backoff. Attempt 1 raises SearchAPIError and retries in 1 second. Attempt 2 raises the same error and retries in 2 seconds. Attempt 3 succeeds and the workflow continues normally. (In LangSmith Studio, you’ll see 3 separate executions of the node with exponential backoff timing.)

This pattern is unsuitable for errors that won’t resolve with retry (like bad API keys or malformed requests), errors that need user input, or errors requiring semantic understanding to fix.

Pattern 2: LLM-Guided Recovery

This pattern stores errors in state and routes to an LLM agent that decides the recovery action. Use it for errors with semantic information an LLM can understand and fix.

We handle this by creating an agent node that uses Command with goto to route dynamically based on state. Instead of raising exceptions, nodes store errors in state and return to the agent:

from langgraph.types import Command

def agent(state: EmailState) -> Command[Literal["get_customer_history", "normalize_email", "draft_response"]]:

"""Agent examines state and decides next action."""

decision = llm.invoke(state) # LLM decides based on state

return Command(goto=decision.next_action)

def get_customer_history(state):

"""Node stores errors instead of raising."""

if has_error:

return {"customer_history": {"error": "..."}} # Store error

return {"customer_history": {...}} # Store result

workflow.add_node("agent", agent)

workflow.add_node("get_customer_history", get_customer_history)

workflow.add_edge("get_customer_history", "agent") # Always route back to agentThe recovery flow cycles through the agent node multiple times:

- First,

get_customer_historyfails due to mixed-case email, stores the error, and routes toagent. - The LLM agent sees the error and decides to call

normalize_email. - After normalizing the email, it routes back to

agent, which decides to retryget_customer_history. This time it succeeds and routes toagentagain. - The agent sees valid data and decides to proceed with

draft_response.

In LangSmith Studio, we can watch the circular path through the agent node and see LLM reasoning for each decision.

Note that the agent’s return type Command[Literal["get_customer_history", "normalize_email", "draft_response"]] explicitly lists all possible routing destinations. This provides type safety and serves as documentation showing the full decision space. If you add new recovery paths, update this type hint.

Use this pattern when error messages contain semantic information LLMs can parse, when multiple potential recovery strategies exist, or when the best action depends on contextual understanding. Avoid it for simple errors with deterministic recovery (use conditional edges instead), errors that need human judgment, or when high-latency is a concern (each agent call requires one LLM inference).

Preventing infinite loops

Since this pattern creates circular routing, add safeguards to prevent infinite loops (e.g., MaxIterationsError):

class EmailState(BaseModel):

# ... other fields ...

iteration_count: int = 0

max_iterations: int = 10

def agent(state: EmailState) -> Command[...]:

# Check iteration limit

if state.iteration_count >= state.max_iterations:

raise MaxIterationsError(f"Agent exceeded {state.max_iterations} iterations")

decision = llm.invoke(state)

return Command(

update={"iteration_count": state.iteration_count + 1},

goto=decision.next_action

)Alternatively, you can also track specific error types or visited actions to detect stuck states.

Pattern 3: Human-in-the-Loop

This pattern uses interrupt() to pause workflow execution and request human input. Use it when missing data only users can provide, handling ambiguous requests, or making high-stakes decisions.

The key is to use interrupt() inside a node to pause execution and compile the workflow with a checkpointer. Resume by invoking with Command(resume=...):

from langgraph.types import interrupt, Command

from langgraph.checkpoint.memory import MemorySaver

def node_with_interrupt(state):

if needs_user_input:

user_data = interrupt({"request": "Please provide X"})

return Command(

update={"field": user_data["field"]},

goto="node_with_interrupt" # Recursive until condition met

)

# Continue normally

return {"result": "..."}

# Compile with checkpointer (required for interrupt/resume)

checkpointer = MemorySaver()

app = workflow.compile(checkpointer=checkpointer)

# Part 1: Trigger interrupt

result = app.invoke(initial_state, config={"configurable": {"thread_id": "1"}})

# Part 2: Resume with user input

result = app.invoke(

Command(resume={"field": "user_value"}),

config={"configurable": {"thread_id": "1"}}

)The node detects missing customer_id, calls interrupt() with a request payload, and the workflow pauses and returns the payload to the caller. After the human provides the customer_id, the workflow resumes from the same node with updated state. The node sees that customer_id now exists and continues normally. Note the recursive pattern: the node calls goto="search_docs" (itself) after getting user input, creating a loop until the condition is satisfied. (In LangSmith Studio, you’ll see the workflow paused at the node with the interrupt payload, then the resumed continuation.)

Use this pattern when you need required data only users have (account IDs, preferences, clarifications), high-risk actions needing approval (delete data, financial transactions), or ambiguous requests needing clarification. Critical requirement: you must use a checkpointer to maintain memory of workflow state between invocations.

Pattern 4: Unexpected Failures

This pattern logs context then re-raises the exception—don’t catch what you can’t handle. Use it for bugs, edge cases, and critical infrastructure failures. In this case, we log state context for debugging, then re-raise the exception without attempting recovery:

def node_with_unexpected_errors(state):

try:

result = risky_operation()

return {"result": result}

except UnexpectedError as e:

# Log context

logger.error(f"Error: {e}, State: {state.dict()}")

# Re-raise - don't recover

raiseWhen the node encounters an unexpected error, it logs state context for debugging, re-raises the exception without attempting recovery, and the workflow fails immediately. LangSmith captures the full state at the failure point. (In LangSmith Studio, you’ll see a red error icon on the failed node with the stack trace and state snapshot.)

Use this pattern for infrastructure failures (database down, API 500 errors), programming bugs (unexpected data types, null references), security violations, or any error where “continuing anyway” would be worse than stopping. Don’t catch exceptions you can’t meaningfully handle—let them bubble up to your monitoring system where they trigger alerts with full context. In production, connect to error monitoring tools like Sentry or Datadog for alerting. LangSmith Studio provides tracing and debugging visibility but isn’t designed for incident response.

Summary

We’ve covered four distinct error handling patterns, each designed for different failure modes. The decision framework boils down to one question: how should the system recover? Transient failures need time, semantic errors need reasoning, missing data needs human input, and unexpected failures need developer attention. Here’s a quick reference mapping common scenarios to their appropriate patterns:

| Scenario | Pattern | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| API timeout | Retry with Backoff | Transient - likely succeeds on retry |

| Rate limit (429) | Retry with Backoff | Temporary - retry after backoff |

| Database query timeout | Retry with Backoff | Connection issue - often resolves quickly |

| Third-party service unavailable (503) | Retry with Backoff | Service may recover within seconds |

| CRM (Customer Relationship Management) returns error message | LLM-Guided Recovery | LLM can adapt response to missing data |

| Invalid email format | LLM-Guided Recovery | LLM can normalize and retry |

| Malformed JSON in API response | LLM-Guided Recovery | LLM can extract data despite formatting issues |

| Ambiguous user query | LLM-Guided Recovery | LLM can reformulate or add context |

| Missing user preference | Human-in-the-Loop | Only user knows their preference |

| Delete confirmation | Human-in-the-Loop | High-stakes action needs approval |

| Payment amount approval | Human-in-the-Loop | Financial decision requires human judgment |

| Account ID for lookup | Human-in-the-Loop | User-specific data only they can provide |

| Database connection lost | Unexpected Failures | Infrastructure issue - can’t recover |

| Null reference error | Unexpected Failures | Programming bug - needs investigation |

| Authentication service down | Unexpected Failures | Critical dependency failure |

| Permission denied on resource | Unexpected Failures | Security/configuration issue needs fixing |

This guide covered four distinct error handling patterns, each designed for different failure modes. Retry with Backoff handles transient failures that resolve automatically with time. LLM-Guided Recovery uses the LLM to decide recovery actions for semantic errors that require reasoning. Human-in-the-Loop pauses workflow execution when missing data or decisions require human input. Unexpected Failures log context and bubble up to developers when the system can’t meaningfully recover.

LangGraph workflows are compiled, meaning node functions lock in after calling .compile(). To test different behaviors, you must rebuild the workflow with nodes_override to swap in alternative node implementations. This design choice is why modular architecture matters—it enables deterministic testing without polluting production code. Test utilities provide controlled error simulation, making it easy to validate recovery behavior from notebooks or CLI.

Use LangSmith Studio to observe workflow execution in real-time. It provides execution traces, state inspection at each step, and full context for debugging errors. For production monitoring and alerting, integrate with dedicated tools like Sentry or Datadog—Studio is excellent for development visibility but not designed for incident response.

Error handling in agent systems is more complex because we have semantic errors that require different recovery patterns than typical software engineering. The key is matching the recovery pattern to error characteristics.

If you found this post useful, you can cite it as:

@article{

hongsupshin-2026-langgraph-error-handling,

author = {Hongsup Shin},

title = {LangGraph Error Handling Patterns in Production},

year = {2026},

month = {1},

day = {12},

howpublished = {\url{https://hongsupshin.github.io}},

journal = {Hongsup Shin's Blog},

url = {https://hongsupshin.github.io/posts/2026-01-12/},

}