Two teams exist in many organizations building AI capabilities: the SDK team builds client libraries and developer tools, and the solutions team builds applications. Both teams want the same thing: successful AI products. But there’s a tension.

The SDK team asks the solutions team to adopt their tools. The solutions team resists: “Too immature, slows us down. We’ll just use the API directly.” The SDK team can’t mature the tools without production use cases. Meanwhile, internal users/engineers, who are eager to build things quickly, just bypass both teams entirely and use OpenAI or Anthropic APIs directly, sometimes with nothing more than a prompt file and a Python script.

Both sides are frustrated, and both sides have valid concerns. The SDK team genuinely wants to help because they’re trying to prevent chaos and technical debt. The solutions team isn’t being difficult because they face demands from users and they’re trying to ship products under real deadlines.

This post examines why internal SDK teams struggle with adoption, even when building technically sound tools, and what actually works based on my experience building and using AI SDKs.

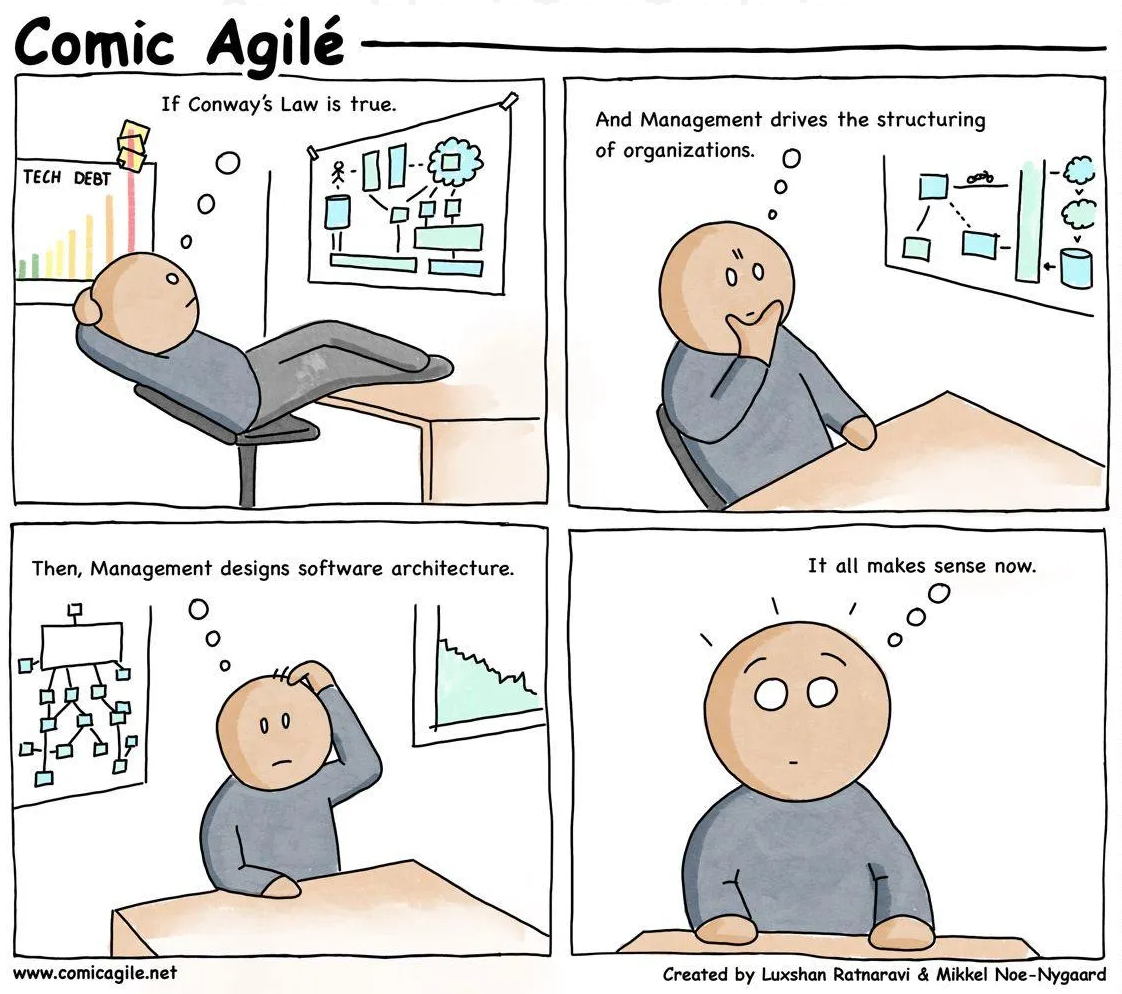

Conway’s Law: Building in Isolation

The typical model looks like this. An SDK team operates separately from solution teams, building an SDK based on what “users should (or would) want” based on some hypotheses. They push adoption without proving that it solves real problems. Features get built speculatively, before patterns emerge from actual use cases, which naturally creates user alienation and resistance. This isn’t malice—it’s an organizational structure problem. The reasoning seems sound: “We need reusable tooling before use cases proliferate. If we don’t build this now, we’ll have chaos later.”

But the consequences are predictable. With no production use cases driving requirements, the SDK team keeps building features based on hypotheticals, leading to over-engineering or feature mismatch. Adoption stays low because for solution engineers, this just feels like another unnecessary layer. The cycle repeats.

The issue isn’t technical capability. The teams are structurally set up to not collaborate effectively. Whether the motivation for an SDK is vendor independence, cost governance, or developer experience, the adoption problem remains the same: you can’t build a good SDK for a problem space you haven’t explored through real applications. One would say we can still build an SDK for general features, but then why would we need this additional layer in the first place?

Conway’s Law is at work here. Team boundaries create tool boundaries. When SDK engineers operate in isolation, they build isolated tools.

“Paved Roads” Rather Than “Golden Paths”

The alternative approach requires SDK engineers to embed with solution teams and build 2-3 real applications themselves first. SDK engineers can extract common patterns into an SDK after they see repetition across use cases. Then, they bring their SDK to maturity by continuing to apply and validate it with new and existing use cases. This embedding approach creates an immediate feedback loop. SDK engineers experience user pain firsthand, not through filtered feature requests. When they’ve used their own tools in production, credibility and adoption come naturally. The solutions team sees them as peers who understand their constraints, not outsiders pushing tools.

This connects to an important engineering concept: “paved road” vs. “golden path.”

- Golden path provides one blessed way. High opinions, low flexibility. The SDK makes strong assumptions about your workflow and enforces them.

- Paved road makes the right thing easy but doesn’t prevent alternatives. Lower opinions, high flexibility. The SDK helps you do common things quickly but doesn’t lock you in.

Both have pros and cons, but for AI development, paved roads are the better choice, at least initially. LLM APIs, frameworks, and best practices shift rapidly, and the whole process requires experimentation: trying different retrieval strategies, testing model combinations, iterating on evaluation approaches. Golden paths lock in workflows before understanding their true utilities. In large organizations, they often become bureaucratic blockers that slow down the very innovation they’re meant to enable.

But paved roads alone can invite chaos. This is where guardrails come in: automated safety nets that constrain consequences without constraining methods. For instance, cost controls like budget alerts and rate limiting prevent runaway spending. Security and compliance measures like audit trails and PII detection prevent data leaks. Observability provides visibility into what’s happening across applications. These guardrails don’t dictate how engineers build. Rather, they protect against what can go wrong.

Golden paths would make sense later once patterns have stabilized and standardization provides clear value. Organizations fail when they try to build mature-stage SDKs at early-stage maturity. If you have fewer than five clear production use cases with high utility, you might not need a comprehensive SDK with golden paths. You need to focus on building applications that work, and pay attention to what hurts.

“But We Need to Scale Fast”

This advice sounds reasonable for small teams. But what about organizations that need to scale AI adoption quickly?

Let’s be real: the pressure is on. Many companies want to ramp up AI across their organizations quickly. They have dozens of ML engineers or data scientists, who need to transition to AI engineering. Every team wants AI work, and leadership is expecting 10x returns on their LLM investments. The tempting response is to build the SDK first so everyone has something to standardize around. But it actually makes things worse because you’re locking in abstractions before understanding the problem space.

The key is to deploy AI engineers to highest-priority use cases immediately without waiting for the SDK. Let them document pain points as they build. After 2-3 apps ship, they will see real patterns, and can extract those specific things. They can then start building focused utilities that address observed pain. Starting with the smallest thing that provides value always works.

I would also suggest not to create a separate SDK team. It is much better to have engineer rotation between app and SDK work, which builds organic collaboration, robust team knowledge, and empathy, all at once. For instance, engineers spend a month building an app, then spend the next month extracting patterns into shared tooling, then back to a new app. This rotation keeps SDK work grounded in reality. Engineers understand both perspectives because they’ve lived both.

But more importantly, management must understand that project selection requires ruthlessness. Not all “high priority” projects are actually good candidates for early AI work. Good candidates have clear, bounded scope, not wishlist-type scope creep. They have easily measurable results and eval setup that can be iterated fast. Most importantly, they need engaged domain experts who collaborate actively, not senior stakeholders who over-promise and then disappear. And these criteria should create healthy competition across teams. Teams that can’t provide clear scopes aren’t suitable for ML/AI adoption. It’s better to learn this early than to commit engineers to projects destined to fail. Organizations that try to skip this learning phase end up rebuilding their SDKs after real applications expose the mismatches.

What to Focus SDK Efforts On

This doesn’t mean all early SDK work is bad. The guardrails discussed earlier are exactly what SDK teams should focus on first; automated safety nets that protect without constraining how engineers build. In my experience, some areas provide high value with low controversy:

Observability and telemetry are good starting points. They address a universal need non-intrusively: cost tracking per query/user/project, performance monitoring for latency/token usage/error rates, and so on. You can add these via decorators without refactoring user code. For example, OpenTelemetry-based instrumentation that wraps any module gives teams visibility without forcing them to change their application logic.

Governance and compliance become critical as applications mature. Audit trails for all LLM interactions, data sanitization and PII detection against potential leaks, budget alerts and spend tracking to prevent cost spirals, and access control and rate limiting against abuse. These protections make everyone’s life easier and guarantee compliance.

Developer experience (DX) improvements should focus on reducing friction. Config templates encode best practices so engineers don’t start from scratch. Better error messages with actionable guidance instead of cryptic stack traces. Idempotency checks prevent duplicate operations. None of these are glamorous, but they’re what engineers actually thank you for.

But I’d recommend NOT abstracting:

LLM provider APIs are too volatile because they change weekly. Let LiteLLM or OpenRouter or similar tools handle this. Your abstraction will lag behind updates and become a bottleneck.

Vector database query languages are evolving rapidly. Whatever abstraction you build will be outdated within months. Give users direct access.

Framework-specific patterns like LangChain or LlamaIndex are moving targets. Don’t wrap them. If users choose those frameworks, they’ve already accepted that dependency.

The principle I’ve found helpful: abstract stable interfaces (authentication, observability, governance) from volatile ones (LLM APIs, retrieval strategies). The SDK should make the boring stuff invisible and stay out of the way for the interesting stuff.

Concrete Example: What Made RAG Wrapper Work

In my experience building AI SDKs, I developed a RAG wrapper library that got organic adoption from engineers despite broader SDK adoption challenges in the organization. When I joined the solutions team after my SDK work, I experienced the resistance to the broader adoption firsthand. Engineers saw it as “yet another layer to learn” with unclear benefits. The SDK team had skipped the teaching phase entirely (releasing docs and expecting adoption without demonstrating value or dogfooding their own tools).

Fortunately, before building the wrapper, I worked with teams building RAG applications. After helping build several different pipelines, patterns emerged. Teams spent hours on boilerplate setup, copying similar code between projects. Every team needed custom preprocessing, but in slightly different ways depending on their document types. This experience helped me build these features:

Config-based quick start emerged from watching teams copy-paste the same 50 lines of setup code. Engineers could get a working RAG pipeline in minutes with YAML config instead of learning a new API. Lower barrier meant more people would try it.

Extensibility via custom preprocessors came after the third team asked “can I customize just the chunking logic?” Inspired by sklearn’s pipeline pattern (familiar to ML engineers and data scientists), users could build their own preprocessing pipeline through the config while keeping the rest of the workflow standard.

Idempotency and duplicate detection came from debugging a team’s duplicate content issue that caused retrieval quality and eval data contamination problems. Content hashing at ingestion time prevented duplicate uploads and flagged potential training/validation data leakage, turning this into a safety net.

Product mindset for internal tools meant treating it like a real product. As a firm believer of good communication, I provided detailed documentation with live step-by-step demos, structured feature requests, and 1:1 support conversations to understand needs before and after building.

The value proposition was straightforward because it had lower activation energy than learning LangChain or LlamaIndex from scratch, but more structure than raw API calls. Engineers could start with a standard pipeline in minutes, then customize specific components (embeddings, chunking, retrieval strategy) without learning an entire framework. For teams that needed RAG but didn’t want to become LangChain experts, this was the middle path.

Adoption happened organically. A few engineers experimented, found it useful, and told others. The features that got the most use were ones I have built to solve friction I have experienced myself. The library wasn’t comprehensive but it did address real pain points users hit repeatedly.

Closing Remarks

The most common mistake organizations make with AI SDKs is treating them as technical problems when they’re actually organizational design problems. You can hire the best engineers, give them all the resources, and still fail if the team structure doesn’t support collaboration between builders and users.

The uncomfortable truth is that most organizations aren’t ready for comprehensive AI SDKs yet. If you have only a couple of production applications with clear scope and utility (and chances are you don’t even have an application that meets the criteria), you don’t need golden-path abstraction layers. You need engineers building things that actually work and documenting the learning. The SDK comes later, extracted from observed patterns rather than hypothetical needs.

This requires patience that conflicts with institutional pressure to “scale AI fast.” Leadership wants standardization now. But premature standardization is worse than no standardization at all because it locks in the wrong patterns leading to technical debt, and creates friction that slows down the innovation.

The question to ask isn’t “Is this SDK technically sound?” but “Have we proven this solves a real problem for actual users?” If you can’t point to specific engineers who asked for specific features based on specific pain points, you’re probably building in isolation. And isolation, however well-intentioned, leads to tools that gather dust.

If you found this post useful, you can cite it as:

@article{

hongsupshin-2026-ai-sdk-adoption,

author = {Hongsup Shin},

title = {The AI SDK Adoption Problem: When Conway's Law Meets AI Engineering},

year = {2026},

month = {1},

day = {24},

howpublished = {\url{https://hongsupshin.github.io}},

journal = {Hongsup Shin's Blog},

url = {https://hongsupshin.github.io/posts/2026-01-24-conway-law/},

}